|

Chicago Was Raised Over Four Feet in the 19th Century to Build Its Sewer |

These reports are from almost 150 years ago and the point of including them in this post is to highlight the striking similarities between what people made of the city in the 19th Century and what people are today calling "The Wild West"... I am speaking of course of the internet.

Our popular culture glorifies upheaval, the days of the Wild West, the brave cowboys and sheriffs who organised posses to thwart the baddies... or the Pirates who had more fun than the Navy, and other counter cultures.

However, it's not quite so exciting when today's Wild West Internet see people who work in retail or call centres and they find that their jobs are lost because of the new frontier that is the Wild West of all things online.

... Nor can it be all that exciting when you are the Founder and staff at Friends Reunited, Myspace, Digg or Reddit when their plans and hopes for an internet gold rush heads south.

But just like the Wild West was tamed, so I'm sure the internet will too... if ideas like the ones in books like #NewPower are adopted.

However, this will mean doing a little more than FELTAG's Matt Hancock (What an astounding success that turned out to be!) or Alex Chalk saying

"Tech Companies need to do more"

(When their organisation is responsible for education and the politicians example online is hardly what I'd term as "Leadership")

Check out these extracts and see if you can spot any similarities with 19th Century Chicago and what people say about the internet and social media today.

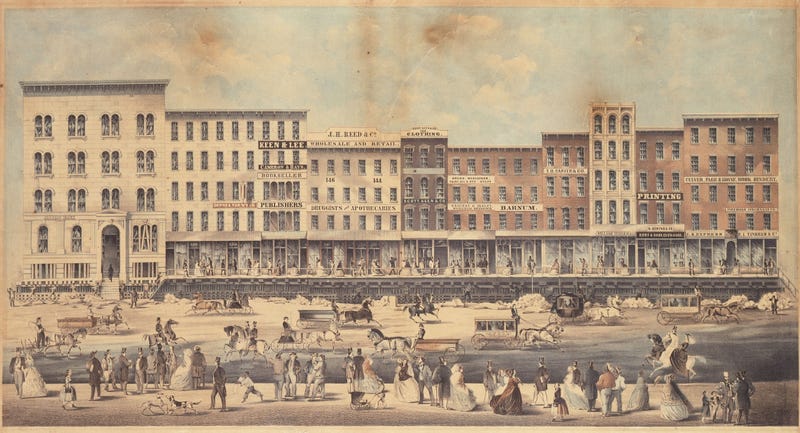

“I shall never forget” wrote the novelist Hamlin Garland of his youthful first visit to Chicago in the 1880’s, “the feeling of dismay with which…I perceived from the car window a huge smoke-cloud which embraced the whole eastern horizon, for this, I was told, was the soaring banner of the great and gloomy inlands metropolis… tangled, thickening webs of steel. As he stepped out into the train station, he was confronted with crowds that seemed as dark and foreboding as the city itself. Writing three decades later about his feelings of fear and alienation at that moment, he sketched a frightening portrait of the hackmen who tried to grab his baggage and drive him for some outrageous fare to his hotel. Their eyes were “cynical,” their hands “clutching, insolent, terrifying,” their faces “remorseless, inhuman and mocking,” their grins “Like those of wolves.” Such were the first people he met in Chicago

Garland’s language is literary and exaggerated, but it outlines the symbolic conventions of the Dark City – in counterpoint to the Fair Country… Repulsed by the dirty atmosphere, stunned at the “the mere thought of a million people,” and fearful of the criminal “dragon’s brood with which the dreadful city was a swarm” in its “dens of vice and houses of greed,” he and his brother spent less than a day exploring Chicago before continuing their railroad journey to the east. And yet, not all was negative about their experience. The tall buildings and the downtown were like none they knew back home, and at every turn they found things they had never seen… Garland concluded, Chicago “was august as well as terrible”

“The manufactories,” wrote Charles Dudley Warner of his visit to Chicago in 1889, “vomit dense clouds of bituminous coal smoke, which settle in black mass… so that one can scarcely see across the streets on a damp day, and the huge buildings loom up in the black sky in ghostly dimness.” Things were no better thirty years later. “Here,” wrote Waldo Frank in 1919, “Is a sooty sky hanging forever lower.” For Frank, the Chicago atmosphere was a nightmare of Dantes Hell, in which the dismembered corpses of the stockyards’ slaughtered animals descended the earth in a perpetual rain of ash: “The sky is a stain: the air is streaked with runnings of grease and smoke. Blanketing the prairie, this fall of filth, like black snow – a storm that does not stop… chimneys stand over the world, and belch blackness upon it. There is no sky now.”

“Exploding in two or three decades from a prairie trading post to a great metropolis, Chicago was among the proudest proofs that the United States was indeed “natures nation.” …Especially in the years following the devastating fire of 1871, when it seemed that the city had miraculously resurrected itself from it’s own ashes, Chicago came to represent the triumph of human will over natural adversity. It was a reminder that America’s seemingly inexhaustible natural resources destined it for greatness, and that nothing could prevent the citizens of this favoured nation from remaking the land after their own image.

Seen in this light, the city became much more compelling. The Italian playwright Giuseppe Giacosa, who had initially called the place “abominable,” finally admitted that its energy and industry had led him to see in it, “a concept of actual life so clear, so open minded, so large and so powerful,” that it made him think better of his earlier disgust. Chicago was destiny, progress, all that was carrying the 19th century toward its appointed future. If the city was unfamiliar, immoral and terrifying, it was also a new life challenging its residents with dreams of worldly success, a landscape in which human triumph over nature had declared anything to be possible. By crossing the boundary from country to city, one could escape the constraints of family and rural life to discover one’s chosen adulthood for oneself. Young people and others came to it from farms and country towns for hundreds of miles around, all searching for the future they believed they would never find at home. In the words of novelist Theodore Dreiser, they were “life hungry” for the vast energy Chicago could offer to their appetites. William Cronon, Natures Metropolis (P9-13)

“During the next 3 years, the village of a few hundred grew to nearly four thousand. At the same time, Chicago’s real estate became some of the most highly valued in the nation. The mid 1830s saw the most intense land speculation in American history, with Chicago at the centre of the vortex. Believing Chicago was about to become the terminus of a major canal, land agents and speculators flooded into town, buying and selling not only empty lots along it’s ill marked streets… stories abounded of men who bought land for more $1-200 in the morning and sold it for several thousand before the sun set. Lots that had sold for $33 in 1829 were going for $100,000 by 1836. Such prices bore no relation to the current economic reality. Only wild hopes for the future could lead people to pay so much for vacant lots in a town where the most promising economic activity consisted of nothing more substantial that buying and selling real estate. Speculators dreamed of what the land might someday be, and gambled immense sums on their faith in a rising market. As the British traveler Harriet Martineau remarked, it was as if “some prevalent mania infected the whole people.”

When the bubble burst in 1837 and the banks called in loans that had little more than hope as their collateral, people who had counted themselves millionaires teetered on the edge of bankruptcy. The real estate market collapsed, so it became impossible to sell land at any price…The great boom years had carried Chicago ever so speedily away from its Indian past and toward its urban future on which the speculators had based their investments; but the end of the boom left the town stranded with its promise largely unfulfilled… after such dramatic early signs of growth, Chicagoans found it all too frustrating to watch the boom grind to a halt. And yet those who had lost their money in the collapse had little choice but to keep their land, earn a living as best they could, and hope their luck would change. They waited a long time. Another decade passed before Chicago began to fulfill the destiny speculators had dreamed for it during the mad years of the land rush.

The speculators urban dream extended to many more places than just Chicago. The land craze of the 1830s was nationwide, part of an upward swing in the business cycle and a dramatic easing of admittedly shaky credit in the wake of Andrew Jackson’s victorious assault on the Second Bank of the United States. As real estate prices skyrocketed, they fueled a manic search for new places in which to invest. Joseph Balestier, a Chicago attorney who had done well for himself by processing land titles during the craze, recalled in 1840 how the speculators had remapped – and redreamed – the Old Northwest until they had covered it with “a chain of almost unbroken of suppositious villages and cities. The whole land seemed staked out and peopled on paper.” Speculators looking for big profits invested in townsites, which always sold at much higher prices than mere agricultural land. Fictive lots on fictive streets in fictive towns became the basis for thousands of transactions whose only justification was a dubious idea expressed on an overly optimistic map. With wonderful irony, Balestier described how speculators scoured the countryside for any site that might conceivably serve as the seed of a future city. If they could find a stream, no matter how muddy or shallow or small, flowing into Lake Michigan – here was a future harbor from which all else would grow… In 1848 a visitor said The Chicago River was “a sluggish, slimy, stream, too lazy to clean itself” It nonetheless had two great virtues. One was its harbor: Bad as it might be, it was still the best available on the southern shore of Lake Michigan…and proximity to the divide between the Great Lakes and Mississippi watersheds. If investors could arrange to dig a canal across the glacial moraine at this point, an inland passage between New York and New Orleans might at last be possible. As early as 1814, Niles Weekly Register in Baltimore predicted a canal at Chicago would make Illinois “The seat of an immense commerce; and a market for the commodities of all regions” …13 years later Congress granted land to the state of Illinois to build the canal…the first mapping of city lots in Chicago in 1930, was a direct consequence of the canal surveys. So was the speculative boom that followed. William Cronon, Natures Metropolis (P30 & 32)

Compare 1830's Chicago with the 1990 DotCom Bubble

“One 40-something grad student that I knew was running 6 different companies in 1999 (usually, its considered weird to be a 40 year old graduate student. Usually its considered insane to start a half-dozen companies at once. But in the late 1990s people could believe that was a winning combination). Everybody should have known that the mania was unsustainable; the anti-business model where they lost money as they grew. But it’s hard to blame people for dancing when the music was playing; irrationality was rational given that appending “.com” to your name could double your value overnight” Peter Thiel, Zero to One

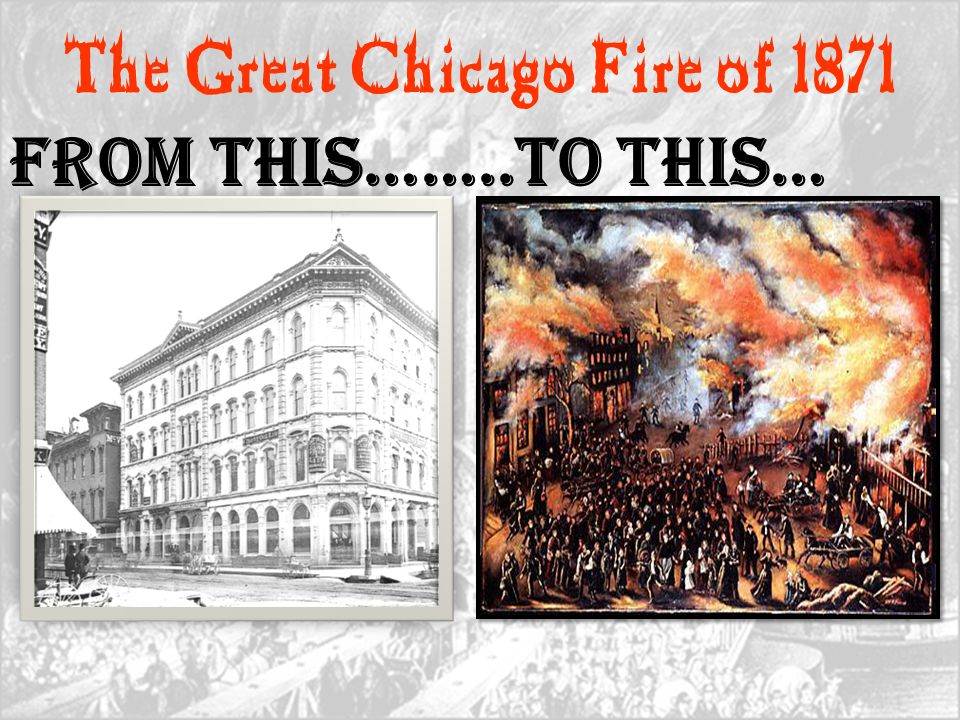

Burning City... Meets A Burning Desire

The morning after the great Chicago fire, a group of merchants stood on Store Street, looking at the smoking remains of what had been their stores. They went into a conference to decide if they would try ti rebuild, or leave Chicago and start over in a more promising part of the country. The reached a decision - all except one- to leave Chicago.

The merchant who decided to stay ad rebuild pointed a finger at the remains of his store, and said, 'Gentlemen, on that very spot I will build the world's greatest store, no matter how many times it may burn down.' The store was built. It stands there today, a towering monument to the power of that state of mind know as a burning desire. The easy thing for Marshal Field to have been exactly what his fellow merchants did. When the going was hard and the future looked dismal, they pulled up and went where the going seemed easier.Napoleon Hill, Think and Grow Rich

In my post about the EdTechBridge Twitter chat, The Greenwich Village of EdTech, I mention how Jane Jacobs details how Boston's North End and Chicago's Back of the Yards District were unslummed.

I'm currently exploring the same ideas in that post - encouraging collaboration and co-creation with all stakeholders - at the moment in a few different ways and using ideas from Sam Conniff Allende's (@SamConniff) "Be More Pirate (And his example with Livity!), as well as Henry Timms (@HenryTimms) & Jeremy Heimans (@Jeremyheimans) "New Power" (@ThisIsNewPower) book.

To be kept up to date with some of these ideas please feel free to complete the forms on the following link:

- Educators UK Edcamp and Edu Collaboration Ideas

- EdTech Developers UK Edcamp and Edu Collaboration Ideas

- He wants Chicago kids to Build the Next Silicon Valley. He's 13

- Why Tech Founder Neal Sales-Griffin is Running for Mayor

No comments:

Post a Comment